(this is post #4 of a series on recovery frameworks. For earlier posts: post one, post two, post three)

Quick news: Substack featured me on their homepage! I’m very grateful for the help getting the word out and the vote of confidence in what I’m doing here. Welcome to all the new folks. I’m glad you’re here.

I’m using this newsletter to explore nuanced accounts of addiction—including the notion that addiction is in all of us—with a focus on what addiction and recovery have to teach us about thriving and flourishing. In the past few months I’ve learned that a lot of you are clinicians and academics, but there are also a lot of smart folks from a variety of backgrounds, so I try to write in a way that is accessible to all while still respecting the actual complexity of these issues—which are, after all, some of the most complex and fascinating challenges in all of psychiatry, philosophy, and human life. So, I’m biased, but I care deeply about these topics and it means a lot to connect with others who find them important too.

I want to hear from you. Please note you can always comment here on Substack, or just write back to my emails, and I really try to read everything. It helps me tremendously to know who you are and what you’re hoping to get out of these writings and podcasts. If you want to support this work, I’m deeply grateful for the paid subscriptions, which help me to make space for Rat Park amid my other responsibilities. Even more than that, though, my chief goal is simply to connect, be helpful, and to hear your feedback as I continue to use this as a space to learn in public.

So far on Rat Park, I’ve written a few longer-form posts about what I’ve been calling “frameworks for understanding recovery.” Looking back, I suppose I’ve spent some time on the complexities of recovery and the terms of the debate: How to walk the line between rigid prescriptions for living well and flexible, individualized accounts? What belongs in a definition of “recovery?” What are the versions of wellness and “happiness” worth working toward? These are all important topics, but today, I wanted to talk a little more practically about how people have tried to lay out frameworks for recovery, how they’re helpful, and how to improve them.

The Ingredients of Recovery

People working toward sobriety, abstinence, recovery, or whatever you want to call it often face a big question. On the threshold of change—considering, for example, whether they need to quit drinking—they often wonder, "is this really for me?"

This is a multifaceted and high-stakes question. We should be compassionate if people get held up here. In my experience, people can get stuck on any number of sub-questions: Can I do it? Is there hope for me? Even if I change, is there a life worth living on the other side? If so, how, exactly? What exactly do I do to make this a livable reality? Most people trying to make big life changes are likely to encounter some versions of these questions, and they can be very, very painful.

I say this to emphasize that how we make sense of recovery is a serious endeavor. On the surface (and in the relevant academic writing) it can sometimes look like playing with definitions. But we can help a lot of people if we can make better sense of recovery, how it works, in a way that is comprehensible and actionable. In a way, clarifying the components of recovery is the hardest part of the project. It’s easy to stop. It’s hard to stay stopped, and recovery is the thing that makes staying stopped worth it.

To this end, a lot of smart people have tried to zoom out on the recovery process and categorize something like a working framework of all the different “ingredients” of recovery. Different efforts use different names—“components,” “factors,” etc—but the point is to organize a list of all the different things that support recovery, wellness, and thriving. After some solid efforts in academic and clinical work, we have a good starting point for something like a framework for recovery.

As a clinician and person in recovery both, I find this kind of organizational framework useful. When meeting a new patient, for example, it’s good to take a step back and make a thorough assessment of all of someone’s barriers and assets. At a simple problem-solving level, the process often identifies good resources or unexpected pathways for change. Clarifying these ingredients is also important for research and academic work, because we need better ways of understanding, measuring, and enabling addiction recovery. Most interesting to me, though, taking a systemic view helps to undo the overly individualized assumptions and stories people often carry about their addictions (e.g., “if only I could have more willpower,” or “I’ve been irresponsible and this is my job to handle on my own.”). If nothing else, this is one of our most crucial tasks, because we often cause so much damage to ourselves and one another by overly individualizing these problems.

Recovery Capital

The most popular organizing framework for recovery today is “recovery capital,” which has been the subject of several academic articles for roughly 2 decades. Recovery capital is usually defined as all the internal and external resources that can help to overcome a substance problem. For example: tangible resources like money and a place to live, personality characteristics, skills, social relationships, etc. Perhaps the best single breakdown of recovery capital is a 2017 systematic review by Emily Hennessy, where she proposed an organizing framework of domains.

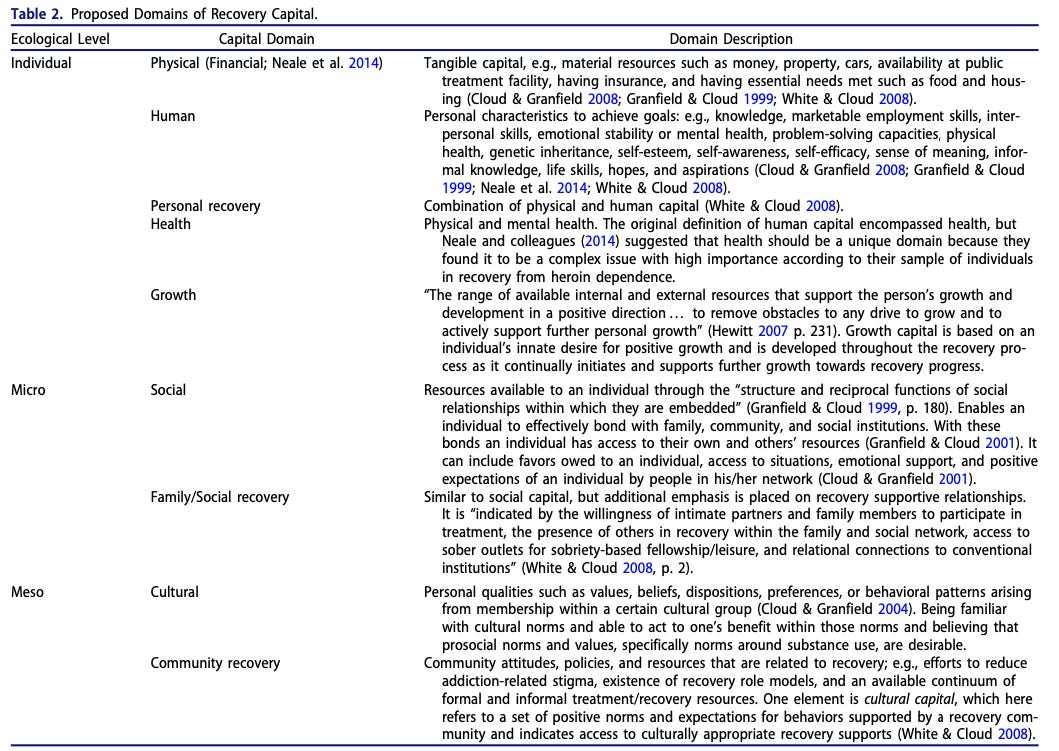

The article is unfortunately paywalled, so I’ll summarize some of the key takeaways. Hennessy categorizes recovery capital into three primary “ecological levels:” individual, micro-, and meso-, each containing different subdomains that contribute to recovery.

At the individual level, the subdomains are physical, human, health, and growth. These subdomains cover money and tangible material resources (physical); knowledge, skills, and emotional stability (human); physical health, and attitudes, aspirations, and motivations for change (growth).

The micro-level focuses on social and family recovery capital. This includes connections at the family, community, and broader social levels, all of which can support people’s access to emotional support, supportive situations, and even positive expectations (i.e., what a healthy community might encourage).

At the meso-level, the cultural subdomain describes broader values, beliefs, and patterns that come from a particular culture’s norms and practices. The community recovery domain, on my read, is an effort to describe essentially political factors, without using the word “political:” things like community policies and resources related to recovery, the availability of treatment, and so forth

I’d suggest this is a great starting point. Consider again our person wondering, “is this for me?” “Can I really change?” Whether they’re considering their own recovery pathways, or getting help from a clinician or counselor, reviewing all the possible barriers and resources can open one’s perspective to all the pathways to change that are available, especially those that go beyond individual effort. Easy to say, hard to do, good to have a rule of thumb to make sense of a complex and dynamic process.

Thinking in systems

What do we really have here, though? We have a list of good ingredients. It’s not entirely clear how important each of those ingredients are, which ones are absolutely necessary, and how they interact. This list is like some of the other efforts I’ve discussed in this “frameworks” series. The list is a useful heuristic, and it’s nice to have a rule of thumb, but it’s perhaps not as rigorous or descriptive as we’d like it to be.

Hennesssy (with David Best) acknowledged as much in a subsequent piece for the journal Addiction in 2022, in which they wrote that the recovery capital literature has been fairly unsystematic, relying mostly on self-report questionnaires, and lacking in foundational theoretical and conceptual underpinnings. Recovery capital research has studied and identified particular factors that might help an individual enter recovery and make a change, but it’s not always clear how this guides the work of a peer, therapist, loved one, or other helper, not to mention policy issues. In the end, “there is an urgent need for conceptual and empirical development to be undertaken in an integrated, systematic way that can offer a viable evidence base to meet this policy need.”

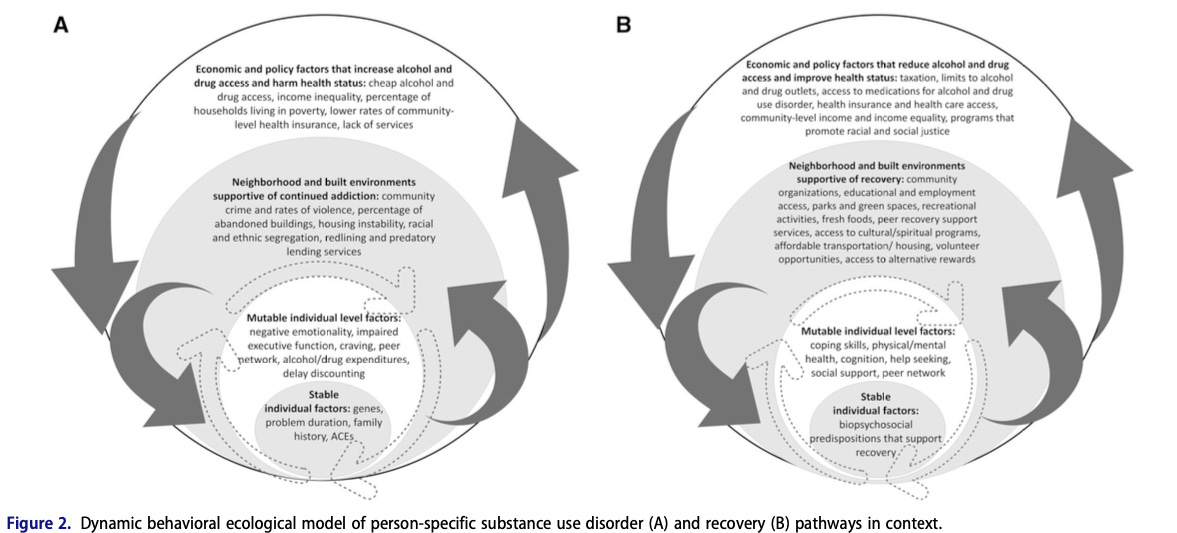

It’s a hairy problem for all of mental health these days to describe a complex, dynamic system. Katie Witkiewitz (a very smart research psychologist at UNM who was the very first guest on my podcast for a reason) has taken a crack at this problem from a somewhat different angle. Earlier this month, she published a new academic article with Jalie Tucker (open access here) that puts even more emphasis on broadening the perspective of recovery beyond the individual. They call their framework a “dynamic behavioral ecological model” and builds it off the Institute of Medicine’s socioecological model. If you’re in the field, the paper is worth reading in full.

The first thing to notice is they are trying to lay the groundwork for moving past the recovery process as a static list of factors. This matters for a lot of reasons, but one clear case is assessing where someone is in their recovery process. How exactly do we measure where someone is in their process, and how does that guide where to focus our efforts? One approach from the recovery capital literature basically tallies up scores from the different levels of recovery capital for an overall numerical measure. A good example of this is the “Assessment of Recovery Capital,” (E.g., “I am satisfied with my involvement with my family,” [micro/community level] “I feel safe and protected where I live,” [individual/physical level] etc.) Witkiewitz and Tucker, however, argue that it’s not enough to take a gross snapshot, or even a snapshot across all these levels, without further understanding how the system is changing and how different aspects of the system interact with one another over time. In a complex system, an individual’s choices and patterns of behavior will evolve in nonlinear and seemingly unpredictable ways.

We’ve all seen transformational, quantum change moments. Someone is hammering away at a problem for a while, apparently stuck, and then things change, suddenly, without any rhyme or reason. Someone struggles with substance problems for years, maybe going to meetings, maybe going to therapy, doing all they can, without any clear progress. Then, one day, they stop, and no one really knows why. In complex and dynamic processes like recovery and behavioral change, there are going to be those emergent and hard-to-predict moments. Spiritual people call that “grace” and move on with their lives, but clinicians and researchers don’t have that luxury. In order to really understand (and to encourage) those moments of change, we need to drill down into the dynamic interactions within and across levels.

Another interesting point here is that the factors that promote recovery are not simply the absence or opposite of the factors that promote substance problems and addiction. Emotional problems or environmental stresses might promote harmful substance use. But taking away those problems and stresses doesn’t assure that someone will transition to recovery. For example—and back to the Rat Park experiment!—you can reduce preference for a harmful substance by enriching the environment with alternative rewards, even if the availability of the harmful substance remains unchanged.

Moving forward

So this is a useful start, but as the best people in the field are actively discussing today, these frameworks are incomplete and need more rigorous and systematic development.

There are at least two major pathways forward here: (1) do more research within the existing recovery research, and (2) look to related fields that have worked out related conceptual and theoretical structures for how change happens. (1) is ongoing and will surely yield some interesting findings, but frankly, I’m surprised there hasn’t been more interest in (2). In fields like general psychiatry, psychotherapy research, and positive psychology, I’d say the discussion of paradigms and conceptual frameworks is a bit more robust and rigorous. There are some tentative steps to find connections here—e.g., between positive psychology and recovery—but I think there’s more that we could do at the level of conceptual synthesis.

So, in my next longer-form post, I’m going to look into those synthetic possibilities a bit further and trace some of the ways that we can draw on those fields to make better sense of addiction, recovery, and processes of change.

For now, I hope it’s helpful to take this zoomed-out view. If you keep the frameworks above in mind, I’d love it if you would let me know if they are helpful, and how. If nothing else, I hope it’s a prompt to be a little less hard on ourselves and one another.

Thanks for reading. If you’re liking this work and want to support it, please share and consider upgrading your subscription.

PS Here’s the embed to my interview with Katie Witkiewitz:

I think the dynamic model is a good start but it seems to leave out a few highly significant factors. In the outer ring, there is no mention of cultural norms around alcohol and alcohol advertising and promotion. In the inner ring, although crime is mentioned, I think the broader idea of safety should be included - e.g to encompass domestic violence, psychological safety. At an individual level, I think self compassion/lack thereof is an essential component and should be called out.

I’m inspired to have a go at my own less technical version! 🙏

nice perspectives, thank-you. also a shocking coincidence!!

I was drawn to ‘flourishing’ simply because we discussed this word at my Caduceus group 2-weeks ago.

I raised the topic after hearing a marvellous Sociologist out of Emory U talk about the concepts from his discipline. He also shared treatment suggestions or preventative measures to moderate symptoms - 5 vitamins, or 5 nonpharm approaches.

Most seem to resemble the fundamentals of Twelve Step Fellowships / SMART recovery

reputable interview source (Canada’s CBC)

interview is around the 19-20min.

https://www.cbc.ca/listen/live-radio/1-63-the-current/clip/16049943-feeling-invisible-you-might-languishing