How AI Reflects and Reinforces Mental Health Stigma

Our paper in BMJ Mental Health: AI-generated imagery often amplifies harmful stereotypes about mental disorders. How models like DALL-E 3 and Midjourney shape public perceptions of mental illness

With some great collaborators, I have a new article out in BMJ Mental Health “AI depictions of psychiatric diagnoses: a preliminary study of generative image outputs in Midjourney V.6 and DALL-E 3” (full text, open access). We explored how AI models portrayed common psychiatric diagnoses: the images they produced often reflected cultural stereotypes and stigmatizing portrayals of psychiatric conditions. We believe this is the first thorough examination of how leading gen AI image models visually depict mental disorders. The practical relevance: AI has the potential to powerfully shape public perceptions of mental health. Simply put, it’s crucial to understand these impacts in mental health contexts, whether you’re a clinician, a policymaker, or just someone trying to make sense of this nebulous field we call mental health. These findings suggest ways forward for responsible development of AI tools and guidelines. And, the outputs these AI tools generate may themselves be an interesting area of research (e.g., for studying collective perceptions of mental disorders), which could point toward better ways of addressing stigma and misinformation.

We are primarily focused on addiction and recovery here at Flourishing After Addiction, where stigma and misinformation are especially important topics!

I was really happy to collaborate on this one with John Torous and his lab—John is the director of the digital psychiatry division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, one of the Harvard affiliates, and I’ve been following his great work for a while.

I don’t think I need to belabor the point that as these AI tools become increasingly accessible and widely used, they will become an even more powerful source of influence and information about mental health. You only need to look at some of the AI-generated art people use here on Substack to see how common it is for AI to shape our visual landscape!

In my own psychiatric practice, I’m already seeing people who turn to AI for advice or even clinical information—a trend that will only grow. The image-generation side of AI is rapidly growing as well. For those that don’t know, about a year ago, OpenAI integrated their DALL-E 3 image generation model into paid versions of ChatGPT, and Midjourney has 16 million users since its launch in 2022. However, there has been little research on the impact of AI-generated images. This study aims to address that gap.

I want to emphasize that our goal here was neither to condemn or promote AI image-generation tools, but rather to understand how they function and to help educate others so we can address this rapidly evolving issue. If you are interested in the practice of mental healthcare today, I think this is an important issue to track.

Below I’ve chosen some excerpts so you can get a high-level view of what we describe in the paper:

Historical Background

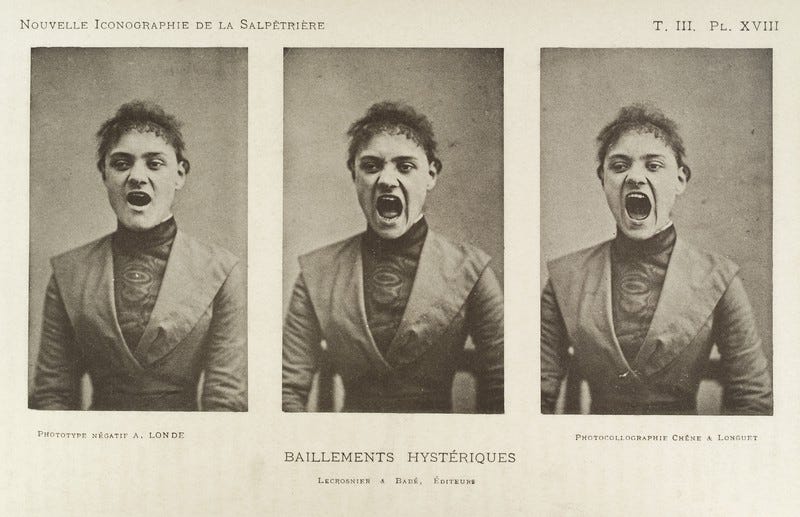

Image-based psychiatric classification (diagnosis) predates modern medicine, being evident in visual artefacts from the Middle Ages onward. As early as the Renaissance ‘the appearance of the individual is seen as a classifiable, interpretable reference to his mental state’. This idea gained momentum with the proliferation of engraving in the 17th and 18th centuries as early psychiatric pioneers produced images of ‘typical cases’ of mental pathology in their diagnostic classifications. The invention of photography in the latter half of the 19th century amplified these ideas further. Most famously, Jean-Martin Charcot used the early medium of photography to ‘systematically’ classify various neurological and psychiatric illnesses giving rise to the (in)famous collection of Salpêtrière photographs of hysteria.

AI is rapidly impacting clinical practice and public perceptions of mental health

The rapid evolution of generative AI technologies has significantly impacted how people access and interpret information including health-related content. Released to the public in November 2022, OpenAI’s ChatGPT reached an estimated 100 million monthly users in just 2 months. Preliminary research has found that, despite its recent introduction, most people are already willing to use ChatGPT for self-diagnosis and trust in ChatGPT’s health-related output rivals trust in Google search results on the same topics.

Our study

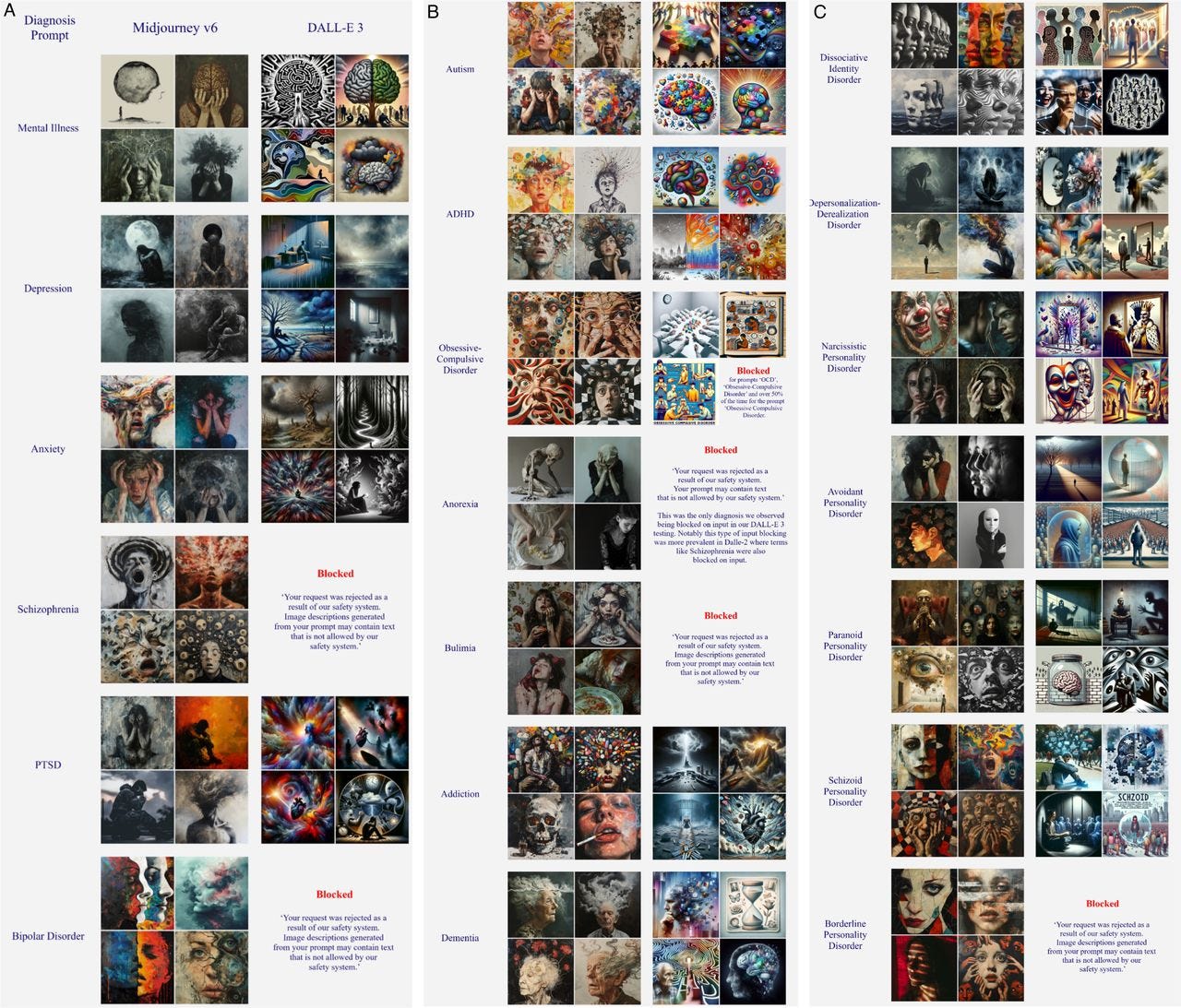

Figure 1 below presents a selection of images generated by Midjourney V.6 and DALL-E 3 when prompted with isolated psychiatric diagnostic terms with no additional qualifiers. We selected these terms to highlight a diverse array of common mental health conditions listed in the WHO’s fact sheet on mental disorders. Exact prompt terms were chosen based on common lay terms for diagnoses (anxiety as opposed to generalised anxiety disorder, PTSD rather than post-traumatic stress disorder) to better capture the search terms likely to be used by patients when seeking mental health information online. A few exceptions were made in cases where the abbreviation was likely too noisy in the source data (OCD, DID, DPDR). For each prompt, we selected the first four successfully generated images for inclusion in figure 1. We attempted up to 10 generations before marking any result as ‘Blocked’.

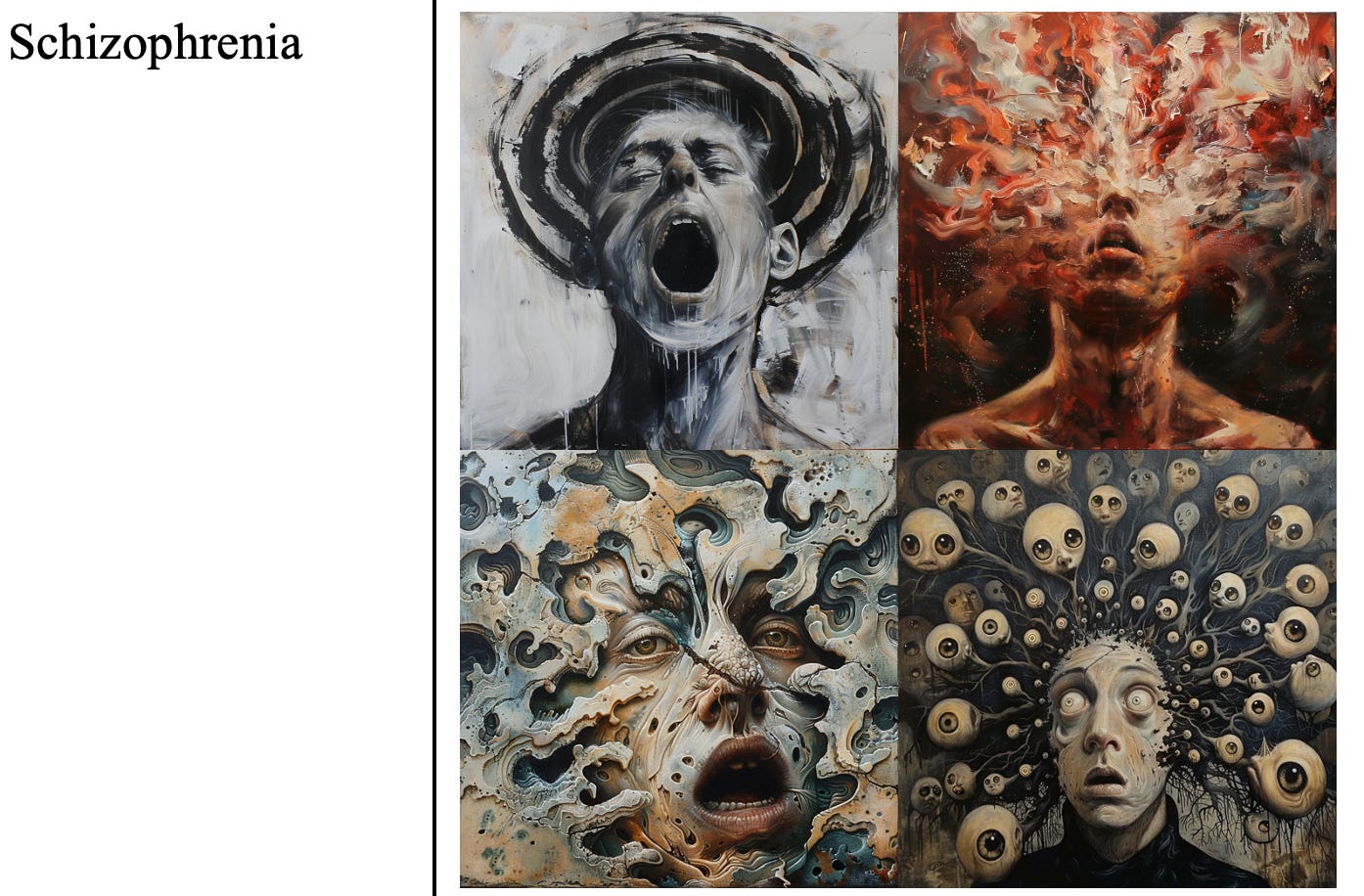

Figure One reveals several striking instances where AI-generated images align with historical visual archetypes of mental illness. Some of these outputs notably reflect the binary classifications of melancholy and mania described by Sander Gilman in his book—Seeing the Insane. He writes ‘Where melancholy is characteristically seated, with sunken head, lethargic, withdrawn, self-enclosed, the maniac is typically contorted, head and limbs thrown out, hyperactive, and exposed’. The frequency with which the term ‘Depression’ produced stereotypically melancholic depictions while the prompt ‘Schizophrenia’ produced maniacal ones is visual evidence of how technological advances can, perhaps inevitably, resurface historical notions. This is the second key lesson: Because generative image models are not moral agents and lack the capacity to reflect on how culture influences psychiatric understanding, it is crucial to address historically rooted bias to understand and mitigate emerging problems.

for example:

What to do?

“There are a few high-level (overlapping and non-exclusive) options for reducing the impact of bias in AI-generated psychiatric images.”

Option 1: we could “ban the models from producing any content when prompted with clinical terminology that professional medical organisations have deemed biased, stigmatising or otherwise harmful.” One problem with this, however, is that blocking certain search terms in this way (as DALL-E 3 did for some psychiatric diagnostic terms in this study) “could amplify stigma by suggesting that the mere depiction of certain mental health conditions is inherently dangerous, shameful or unsuitable for public viewing.”

Option 2: “demand that generative AI companies hire clinicians to expand on existing prompt manipulation techniques to minimise harm.”

Frankly, we thought these two options were both “unrealistic and unlikely to resolve the fundamental problems posed by generative image technologies. Both strategies rely either on top-down, specific legislative regulation or on industry self-regulation, both of which are unlikely to occur for such a niche concern within a heterogeneous, globally dispersed and rapidly developing AI marketplace.” The most realistic route forward centers on:

Option 3: identifying the specific biases present in AI image models, understanding their roots, and respond to them flexibly and in context, both at the clinical and the policy and research levels, including “proactive collaboration between researchers, clinicians, professional organisations, tech companies and those with lived experience.”

We have a few considerations in the paper for future directions, including reflections on how to enhance mental health literacy and how to study these dynamics better. At the very least, studying how AI represents mental disorders will grant us new perspectives on how these conditions are (mis)understood in the broader culture.

At the level of bioethics, one concrete end goal would be to work toward “better” representations. “Defining what would be a ‘better’ representation is complex and subjective; however, we suggest it should at a minimum avoid harm, minimise stigma and otherwise be in reasonable alignment with scientific and professional clinical judgement.” This could be an interesting area of future development.

In summary…

Generative AI models are here, and they’re increasingly a part of our lives, but they are far from reliable sources for clinical information or insight. “They reflect current perceptions, historical inaccuracies and linguistic biases—a combination that can shape public understanding of psychiatric conditions.” It’s crucial to reflect on where these outputs come from to educate ourselves and our patients. At the same time, AI outputs are a useful focus of study: “subjective, crowd-sourced interpretations offer a unique window into collective perceptions of mental disorders, providing valuable data for scientific inquiry and potential pathways for addressing stigma and misinformation in the field of psychiatry.”

If you’re finding this newsletter useful, please consider sharing this post with someone else you think would benefit.

Really interesting.

Fascinating research. It's easy to see how this can affect end users online using AI gen to self diagnose or just gain information about their disorder/symptoms, but we just need to be aware of the bias/caricature/stereotype (as you say in solution 3). imho AI will be a huge boon in medical informatics with regards to crunching the big data of online testimonials, forums, reddit, etc., to help advance the field of mental illness and access to therapy (with huge caveats of course, 'robo-therapist' is a rather dystopian concept lol).